Christopher Renfro — The Two Eighty Project

Since he was a small child, Christopher has had an innate connection to nature. His fondest memories growing up are those of the woods of Germany - in their depths, he would explore day in, day out, observing the rhythms of Mother Nature. He learnt quickly how to dial into his inner compass and would never get lost.

Through twists and turns of adult life, Christopher never forgot that forest. It wasn’t until he took a job in the restaurant industry, however, that he began to connect the feeling he’d had amongst the trees to something tangible in his hand: a bottle of wine.

It was the start of not just a path, but a highway of discovery. With the unbeatable combination of determination and ambition, he is now the vineyard manager of a plot of vines in San Francisco. It doesn’t stop there: the vineyard sits next to blocks of apartments that are largely home to people from disadvantaged backgrounds, and Christopher is building an educational program to introduce them to the world of viticulture.

Speaking to Christopher and seeing what he has already achieved as a young man fills us with excitement, and some of that determination was definitely imprinted onto us, too. Here’s his story.

Christopher Renfro

Meet Christopher

Christopher moved to San Francisco as a young adult to attend school for Product Design, but instead took a design position working at American Apparel designing and building their stores. However, he became subject to some horrendous racial slurs and found himself in a lawsuit. Although he won, it didn’t go well; lawyers lied to him and contracts were changed behind the scenes.

“Some sneaky stuff was done. I was supposed to get 60/40 dispersal, but they changed it. An arbitrator awarded my lawyer team $320K and tried to give me $30K, so I complained and got $100K, but was initially supposed to get over $200K. It was a crazy feeling and it completely threw me, I was thinking, WHAT is going on in this world?!”

He took some time out to plan what would be next for his career path. He had some experience working in organic grocery stores, so did some work at Rainbow Grocery in San Francisco, where he found himself really excited about the notion of a co-op; surrounding himself with lots of people that believed in different types of justice - from food justice to Trans Rights.

In 2010, he decided to go to school for horticulture, and went to work at various nurseries as well as an indoor flower conservatory, which he loved. Eventually, he found himself in the restaurant industry, working in a front of house position. He began learning about wine, and soon fell down the rabbit hole of researching and learning about producers.

“I was so interested by it all. I was learning about these people, mainly in Europe, being given this gift of land which came with a prestigious job, and there were all these Châteaux… I was like wow, that’s so cool, but also - Black people don’t have anything like that. It really made me think - there’s no Black people involved in this world. I hadn’t seen a single bottle of wine made by a Black person.”

He got a job at a restaurant called LihoLiho, where he got into wine training and began to visit vineyards and wineries. It was Ted Lemon’s Littorai in Sonoma that really piqued his interest:

“Seeing a biodynamic vineyard was really cool. Growing up, I had studied George Washington Carver, and this seemed very close to that - regenerative agriculture before it was called regenerative agriculture.”

At the same time, however, the world of biodynamic farming frustrated him, as it was very similar to practices that African communities have been carrying out for centuries, yet this biodynamic wine world didn’t credit Black people. Rather, it was very white. That spurred him on.

“I remember thinking wow, this is awesome. Not only is it a privilege to work this way - biodynamically and regeneratively - but there’s also this hippy lifestyle that comes with it. Not only are there not many Black people in farming, but there definitely aren’t any doing this, but this is closer to what I’ve always been interested in.”

As he reflects, it feels like speaking to someone who has created all the jigsaw pieces of his life’s puzzle and is now fitting them together.

“As a child, I was raised in Germany. I would walk into the forest backwards, watching the entrance and paying attention to every detail, so I could always find my way back. I noted the seasons, watched animals interact with each other… I was taking in how everything coexisted. I understood even back then that this was the path I was going to take. The reason I’m able to survive in cities now is because I taught myself to survive in forests as a kid.”

It’s an instinct that’s always stayed with him; to the extent that for the most part he doesn’t even need a compass. He understands light and nature in a way that sadly most human beings have become disconnected from.

“Fast forward to Littorai, I was like - this is my jam. I began looking around for land, as I knew I wanted to become a farmer of some sort… perhaps raise pigs or goats… but the wine part was just so cool. It’s like the sexier part of agriculture.”

Ted gave him a vine cutting from Littorai, and Christopher took it back to his house.

“In the car back, my colleagues were like, you’ll never get this to grow. But I did. And right there in my mind, I knew - I can make anything grow.”

The thought of working in viticulture continually tapped at his mind. He had heard about a vineyard in San Francisco called Neighbourhood Vineyards at the time, and tried to reach out to them in 2018, but never heard back. So, he decided to walk to this urban vineyard in December 2019 to see if he could meet anyone there, to ask if he could take a cutting. When he arrived, he realised that it was semi-dilapidated and overgrown; grapes from the previous harvest were still hanging dead on the vine. He found out that it had been abandoned and he should call the farm manager, so he did. He got through to them, introduced himself, and explained that he was interested in becoming a farmer in the city and would love to take over the tending of the vines if possible. A week later, they came back to him with a yes.

“I immediately jumped on it. I began speaking to all the people I’d met in the industry, as well as Googling things and figuring it out on my own… I thought to myself - if I’m going to do this, I’m not going to go to school for it, I have a vineyard right here and I can teach myself! All the information is already out there in the world, I just needed to start calling people.”

Mimi Casteel and Steve Matthiason, both renowned regenerative viticulturists, gave him lots of information about how to care for the vines. Philip Cuadra showed him how to prune.

“In my mind, I knew this is what I want to do for the African American community. The vineyard is right next to a housing project called Alemany Apartments, and it’s right off the 280 Highway. I thought about it, and the 280 Project was the perfect name: a community project to give youth and people from the apartments an opportunity to learn viticulture. I’ve had people come from the community to talk to me, and to volunteer, as well as Queer people and Trans people. The next step is figuring out how to use the vineyard more as a formal education site.”

So, he has begun working on a curriculum that aims to teach 5-10 people about viticulture. He has been speaking to people from UC Davis, as well as winemakers such as the aforementioned Steve Matthiason, to figure out a structured course that involves specific viticultural teaching days, as well as visits to other vineyards to see varying practices - from conventional, to organic, to biodynamic & regenerative.

“It would be awesome to even be able to visit Screaming Eagle…”

The goal will be to show the viticulture students what’s possible in the world of wine. The California industry is an enormous one (almost 900,000 acres are planted to vineyards), so there is no lack of jobs. Christopher explains,

“The issue right now with this current president is that we don’t have the workforce to rely upon due to ICE. It’s an opportunity to get Black people back into agriculture and to give them good jobs - a foreman at a vineyard can earn $85/90K a year. That’s a really well-paid job. Even just starting out, you can make $17/20 an hour, and it keeps going up. I figured this is something I could do in terms of actually being able to create real jobs. As a kid, I totally would have taken that job, and who knows where I would be now if I’d had that opportunity?”

It’s inspiring and tangible. We can tell that Christopher’s mind doesn’t stop whirring; this is the beginning of something big. As well as working to uplift his local community, he also wants to eventually help incarcerated people. He says,

“Incarcerated people should still have a good quality of life and learn in a restorative way, so that when they come out, they can be productive - both for themselves, and for society. I’d like to be able to create viticultural programs in prisons. When they come out, they could be really deep into viticulture. One day, I’d love to have my own land and be able to hire people that were formerly incarcerated, and then help them to get their own properties.”

The opportunities are endless.

He also comments that the world of wine is an uplifting one from a sensory perspective. It’s true; we reflect on how good it is for the soul to look out at a vineyard.

“Wine is so boujee. If you’re on a beautiful property, that can really raise the esteem of people. It makes you feel good. A lot of Latin families I meet; the kids and families are super proud. I think if I can spread that notion and that work, it’ll be a very positive thing. Eventually one day it won’t be about being a Black winemaker, or a Man or Woman Winemaker, it’ll just be Winemaker.”

He also hopes that the future will see new labour laws in place.

“You can't just be the overseer of a plantation; you have to give people health insurance and credibility. The owner should also tell their stories, their website shouldn’t just be about them, it should have the whole team on it in pictures too.”

The Vineyard

Christopher’s plot of vines on Alemany Farms has given him an incredible learning experience that reminds him of how he learnt about the world as a kid:

“When we’re children we pick and pull from all of our friends’ different skills and take ideas from things we admire. We want to learn. It’s just like that… I like this part of biodynamic farming, and that aspect of regenerative agriculture, and if you have water on your property there’s the idea of aquaculture. There is no one way to farm vines.”

He is frustrated when he sees badly treated vineyards.

“Seeing vineyards that look like they’re dying, or even dead, has been a very eye-opening experience for me. The vines might be beautiful, but everything else around is dead. It’s like, man… What are you spraying on them? What is your connection to this land? You have such a privilege and responsibility to this land and it’s like you don’t even care. You’re killing its ecosystem. There are these giant wine communities all doing that; they’re all just copying each other.”

Christopher’s vineyard approach revolves around life:

“It’s super wild, coyotes run through it, birds are everywhere. I'm just always throwing seeds into the ground, trying to create cover crops, and one day when I get a bigger piece of land, I intend to have loads of animals. I want there to be chickens to eat the insects, pigs, etc.”

As we enter winter 2020, Christopher is already thinking ahead to pruning techniques and wants to experiment. He’s also thinking about natural approaches to tackle powdery mildew and other diseases. As it’s a small vineyard, he sees it as a place to experiment and focus on educating himself.

“I can prune these vines or leave them unpruned. I can leave just one or two buds on a vine. What will that mean for the vine? How am I going to change this world by paying attention to it? How many notebooks will I have at the end of this journey of everything I’ve been studying and paying attention to?”

He already has a field guide and many notebooks full.

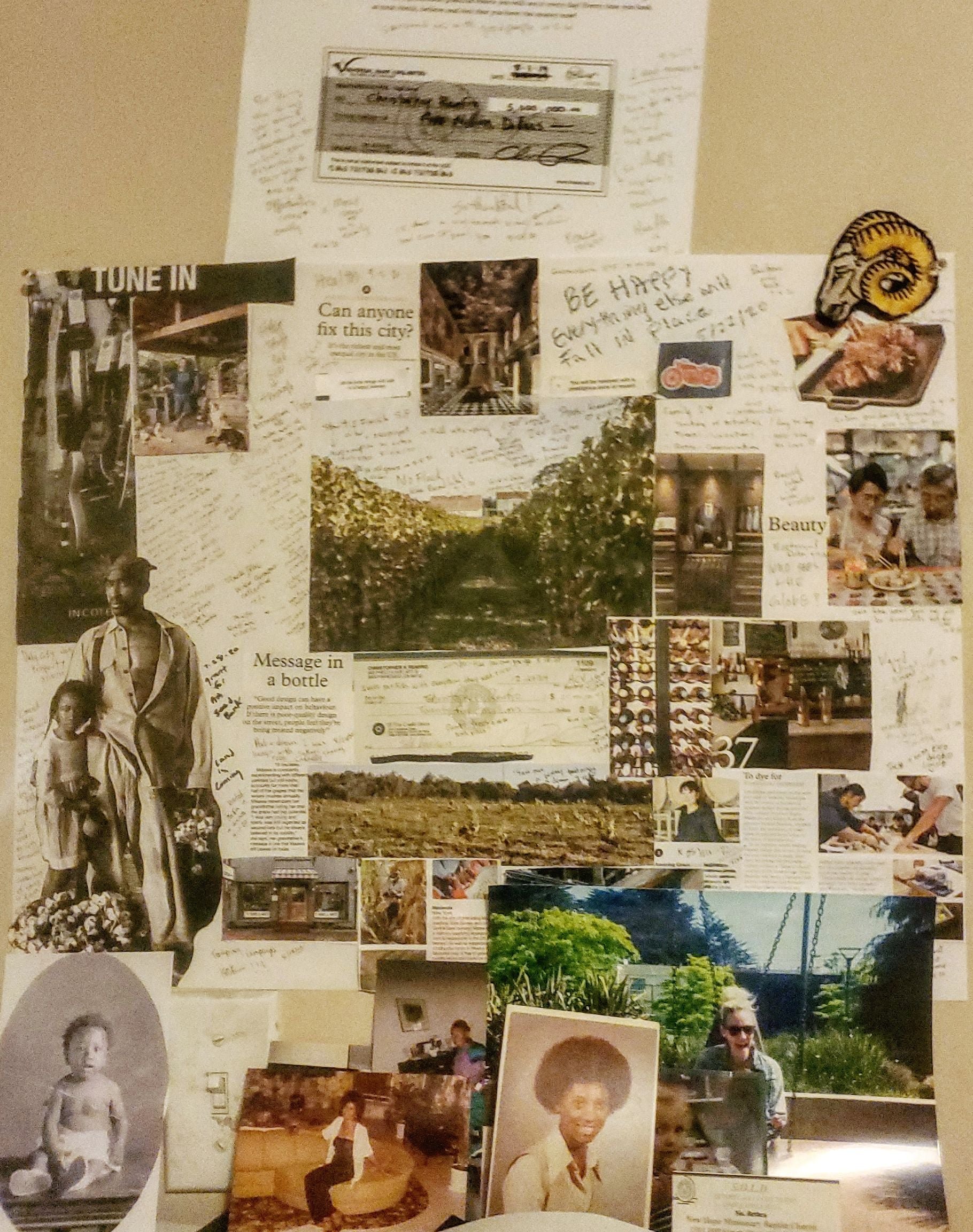

“I do like a lot of vision board stuff. Visually seeing things and putting pen to paper is like solidifying history. You're taking a picture with your hands and your mind at the same time.”

The vineyard is 99% Pinot Noir, with a little part of Roger's Red Wild Grape - Vitis Californica - which he planted himself. He’s incredibly excited about the native grapes of California and is learning about them together with friend Matthew, who documents them in detail on his Instagram account @vitis_californica. He has brought some cuttings to Christopher.

“I’m very interested in native grapes because of what climate change is doing to our country.”

He also read about the Japanese variety Koshu in Monocle magazine a couple of years ago:

“I saw this grape variety and thought, wow this is amazing! I’ve always wanted to go to Japan. I really admire Japanese people, their culture and their growing methods, so I saw this grape and put it on my vision board, thinking - I want to be the person that grows Koshu in America.”

He reached out to a Japanese winery who suggested that he speak to UC Davis. He already knew Steve Matthiason, who was a UC Davis alum. Steve introduced him to Elizabeth Forrestel, who told him that they have Koshu in the UC Davis laboratory. She told him that nobody has planted it yet in California, and that he could have some once it’s been through the quarantine period.

That led to a whole new conversation about rootstock decisions and ideas for grafting. While Christopher was picking up vegetables from the greenhouse at Alemany to bring to the local community, which he does once a month, Elizabeth stopped by and dropped off the rootstock cuttings. He was so excited to come back and discover the bag: gifts of vegetation.

The Wines

When it came to picking the fruit from the 65 vines on the Alemany Farms vineyard for the first vintage of the Two Eighty Project, unfortunately many of the grapes were already missing or destroyed as it’s on public property. They got permission to put up a sign to ask people to please not pick them, and hence were able to save some. Christophers’ two daughters crushed the grapes with their feet, and the juice was left to ferment naturally in glass carboys. It was bottled (all two and a half bottles of it!) on the 8th October, and they will auction off one and a half bottles for a Go Fund Me page. We’ll be bidding.

His friend Stephanie Tonnoir, who works for Zev Rovine Selections, joined for the harvest. Together, they went to visit various growers in California to see and help out at harvests, and many of the growers gave Christopher a couple of buckets’ worth of grapes.

“Now I have a kitchen full of ten six-gallon carboys that are from all of these historic sites in California, that I got for free. I did a fundraiser, we made $7K, and I didn't spend a single dollar on grapes, so it can all go to licencing and things like that.”

The winemaking part is the easy bit. Christopher says,

“Krista Scruggs, a winemaker from Vermont, calls it Just Fucking Fermented Juice. And man, it’s true. It’s alcoholic juice in a bottle.”

Next, Christopher is figuring out how to begin fundraising for a larger property.

“If I can get this, I’m going to put myself and Black People on the map. I’ll put San Francisco on the map. I want to change the urban wine scene and make it real; grow grapes and sell wine here.”

He has ambitions to create a co-op style neighbourhood winery where people can come and go - and learn - as they please. Members would be able to do vintages there, and even participate in exchange programs with other wineries around the world.

He also wants to tackle the food scene and bring back the seeds of the Black communities:

“The thing I hope to do through agriculture one day is to break the monoculture of the food system. The contribution of Black people in America has been stripped away at the food level, to the point where we don’t remember certain ingredients and spices. It’s almost been lost. I’d love to start a seed share to bring back indigenous African varieties and to grow them here, and to keep them going around America. Think about what that could do for the food and restaurant industry - for people that come from different places in the world. They could tap back into menus and recipes that were lost.”

Another goal is to see an entire community of Black winemakers formed; something Christopher likens to the Great Gatsby in spirit.

“It’s just beginning. I see a very long road in this. I hope to eventually kind of create something like a Black AVA, a Black wine growing region where people feel safe, where they have all the tools like people do in the white community. People could help each other; whether lending their press, or a bottling machine. There's an area in California called Lake County. I see it as this area that’s barren, and land is very cheap right now. There are a few wineries and vineyards out there. Imagine if that's the place! Then imagine one day that’s where you’ll find Black people growing wine, having beautiful, old school convertible cars, driving around the lakes, greeting each other and saying, Oh, you should go see my friend's winery over there.”

We’re nodding, transfixed.

“If I've already imagined it, then it's totally possible, you know what I mean?”

We do. In fact, it’s hard to remember a conversation that’s inspired us as much.

“I'm glad that I actually get to be the person that grows wine and will become a viticulture expert. I feel like to me that is bigger than owning the grocery store or the wine shop. Without the grower, you wouldn’t have the wine.”

[Originally published in November 2020]